In recent years, Kristi Finney-Dunn has become a leading voice in Portland’s transportation scene. With a gripping story of personal tragedy, she’s invited to speak at public policy summits, street demonstrations and city council hearings. For local media, she’s become a go-to authority on active transport and road safety.

Others who’ve been impacted by traffic violence envy her resilience. But that’s just one side of the story. “When people see me talk, they’re seeing me at my strongest,” she assures. “They’re not seeing me at those moments when I’m curled up and burying my head and crying about it. Those moments don’t come all that frequently, but when they do come, they’re just as bad as the first few days.”

Kristi’s thinking back to the early morning hours of August 12, 2011, when her oldest son Dustin was struck and killed in a drunken hit-and-run in East Portland.

That night the 28-year-old was riding on SE Division near 85th Avenue when a car came up from behind, veered into the marked bike lane and struck not only Dustin but a second cyclist riding 60 feet ahead. The second rider walked away with minor injuries, but Dustin wasn’t so lucky. On impact, he flew 175 feet and died instantly of blunt-force head trauma.

The 18-year-old driver fled the scene but got less than a mile down the road before ditching his car, which sustained massive damage in the crash. Police picked him up a few blocks away and measured his blood-alcohol level at more than double the legal limit.

Kristi found out at 5 a.m., when a chaplain knocked on her door in Vancouver. After that, Kristi set about the grim task of telling Dustin’s three siblings, two still living at home or nearby and one who lived in Georgia. “I felt terrible for him,” Kristi says. “He’d just lost his older brother, and he was all by himself out there.”

THE FIGHT WAS ON

After the driver was convicted of negligent homicide and sentenced to five years of prison, Kristi finally began to grieve Dustin’s death and process what had happened to him. She devoured every article and blog post she could find about the crash. Dustin was a nature lover who loved cycling because it was good for the environment. But many who read about his death did not appreciate that. “What really got me were the comments,” Kristi said. “Oh, why was he riding at night? Why wasn’t he wearing a helmet? And I was thinking, ‘No, he didn’t die because he wasn’t wearing a helmet, he died because a drunk 18-year-old drove into the bike lane and hit him!’”

The fight was on. Kristi started up a blog about her experience, and made a couple dead-end efforts to fight hit-and-run driving. She discovered Trauma Nurses Talk Tough, a program at Legacy Emanuel Medical Center that educates people charged with DUI or high-risk driving about the impacts of traffic violence. In the program’s “victim-impact” sessions, people who’ve suffered losses in road crashes relate their personal stories to irresponsible drivers. Panelists include surviving family members like Kristi as well as those who’ve been physically maimed in traffic crashes.

Kristi, who has a day job in social services, speaks at a half dozen panel sessions per month. Her audiences run from 40 to 300 people, depending on which of six counties she speaks in. Every audience is a mixed bag. Every one includes a few hard cases who believe their driving is fine — they just had the bad luck to get a DUI. But there are also a few people who break down crying. These tragedies could have been on their heads. Some will come come up and give Kristi a teary embrace. “Sometimes, they won’t stop hugging you!” she says.

WORKING WITH A PERPETRATOR

In this work, the person who’s left the deepest impression on Kristi is a fellow panelist who had caused a crash. In that incident, which netted him eight years in prison, he ran into a family car and killed a mother and two children. The father survived with injuries.

Although Kristi has good reason to detest such a man, she says he’s touched her heart like no other speaker. The man describes how he still thinks about the surviving father and how he must miss his wife and kids every day. As Kristi says, “What I got from his saying that was that he’s truly trying to understand our feelings. It’s not just about him, that I did this thing, I made a mistake, I killed a couple people. It’s as if he’s really trying to understand that other person and how horrible it was.”

Along with the impact panels, Kristi represents traffic violence victims as part of the City of Portland’s Vision Zero Task Force. This is an advisory body guiding implementation of a new policy to eliminate traffic road deaths in Portland by 2025. The group meets formally four times per year.

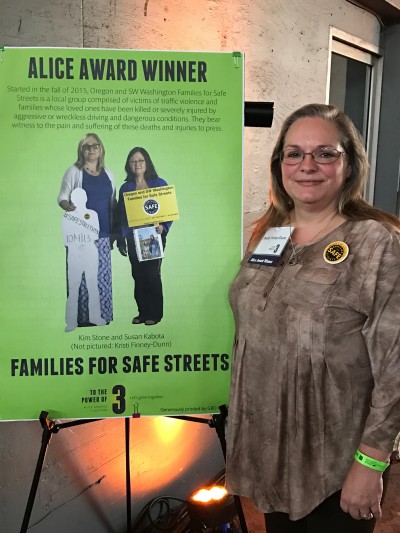

And then there’s her work for Oregon and SW Washington Families for Safe Streets, which she convened in 2015 to both advocate and care for victims of traffic violence. The group is modeled on a pioneering organization in New York City and is now one of seven in North America.

As she found with the hit-and-run victims group, it is a struggle getting people to speak out about experiences that have caused such anguish. Nevertheless, when they do speak out, decision-makers tend to listen. An emergency speed limit reduction on SE Division, the street where Dustin and many others have died in traffic violence, came about in large part because of Families for Safe Streets’ no-holds-barred activism.

One motivator for Kristi’s advocacy is to keep the memory of Dustin alive. “Dustin was an advocate for causes that he cared about,” Kristi says. “Dustin wasn’t being quiet about his life and I’m not going to be either.”